Agroecology: a sustainable way to feed the world and preserve our roots

October, World Food Month, brings us the urgency of reflecting on the issue of hunger, as well as thinking about possible solutions to end this scourge.

Islândia Bezerra,

Extension worker, researcher and associate professor at the Faculty of Nutrition of the Federal University of Alagoas. She is part of the Federal Government’s team in the Dialogues Directorate of the National Secretariat for Social Dialogues and Articulation of Public Policies.

Reflecting, listening, talking and writing about hunger is difficult and challenging. Especially when the food, the preparations, the nutrients, as well as the consistencies, the colors, the smells, the tastes, the food memories represent the culture of a people and therefore the centrality of being and being in society.

The challenge is also expressed in defining the term hunger. In 1946, Josué de Castro shouted to the world that hunger (not having food to eat or not having the means to produce and/or buy food) is an economic, social and, above all, political phenomenon. Decades later, this definition of the term came in the song by the band Titãs:“we don’t just want food, we want food, fun and art“. Almost 40 years on from these thought-provoking lyrics and melodies, talking about food is more topical and necessary than it was at the time of its release.

Hunger is present in the lives of 33 million Brazilians, according to the Brazilian Research Network on Food and Nutritional Sovereignty and Security (Rede PENSSAN). According to the UN, around 828 million people in the world started living with hunger in 2021, and this projection is set to increase.

But it’s not enough to think of this phenomenon as a challenge, without challenging ourselves (the redundancy here is deliberate) to think and act to solve it. Revisiting Titãs’“we don’t just want food, we want life as life wants it”, I ask: how does life want life?

In a context of a climate crisis that is deepening as a result of a hegemonic food system that works to sicken, mutilate, contaminate, expel, expropriate and kill people and nature, we have a possible way forward: agroecologyAgroecology is a thread full of knowledge, know-how and practices that weaves a tangled and complex web of lives. But we need to do more to materialize “life as life wantsit”.

Life wants food, adequate and healthy preparations that are culturally referenced and, above all, biodiverse and that bring with them, in life and on the plate, the colors, smells and flavors of our biomes:

From the Amazon, which brings its ingredients in preparations of fish, vegetables and tubers that pulsate and tremble like the diversity of ancestral knowledge to everyday dishes, as well as agroecology in the region that drives and strengthens these practices;

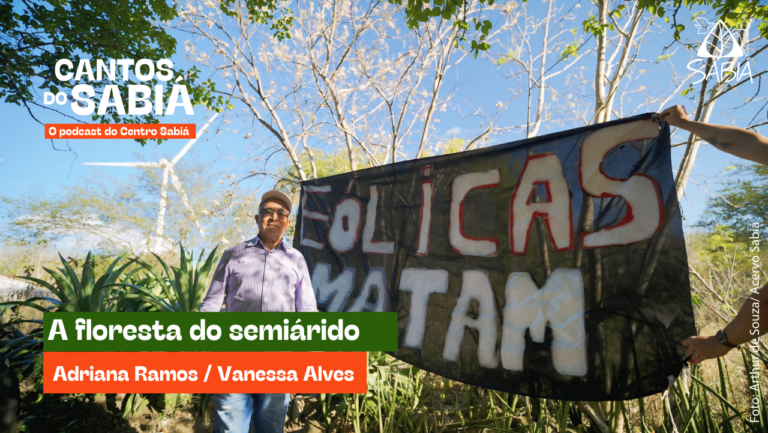

From the Caatinga, which contains flavors, smells and textures that are unique to the place, but which, due to the current predatory model, has been depleting these riches, and agroecology presents itself as the path to a possible solution;

From the Cerrado and the Pantanal (a transitional biome), biomes that cross geographically delimited states, but which find in “root” food the marked presence of fruits, roots, seeds, nuts, which fill the eyes, the mouth and the belly (as we say here in our northeastern region). Agroecology in these biomes has rescued production-eating practices that subvert the logic of the surrounding monocultures.

From the Atlantic Forest – this diverse and threatened biome represents a real and urgent need to strengthen agroecology, simply because it is LIFE. Certainly, if it is preserved, it will play a decisive role in the fight against hunger.

From the Pampa – despite its lesser abundance in terms of species varieties, it is from this place that Brazil experiences aromas and flavors that express diverse cultures, but which also suffer from monoculture processes. On the other hand, agroecology in this biome has been rescuing processes of reconnection between producing and eating, transforming lives and territories.

Among the riches of the biomes, we know one thing for sure: ending hunger means preserving the most valuable things we have: biomes and cultures. We are made of food, of preparations that bring with them stories, recipes, memories – they are not produced on the shelves of markets and supermarkets. They are raised, fed and nourished in the backyards, on the farm, in the collective areas of production and eating, on the plots of agrarian reform settlements, but also in the areas on the outskirts of large urban centers where agroecology produces new relationships between society and nature, and between society and itself. Agroecology as a possible solution to end world hunger is no utopia. It’s about preserving your own existence.

Nothing found.