The Brazilian semi-arid region as a global example of climate adaptation

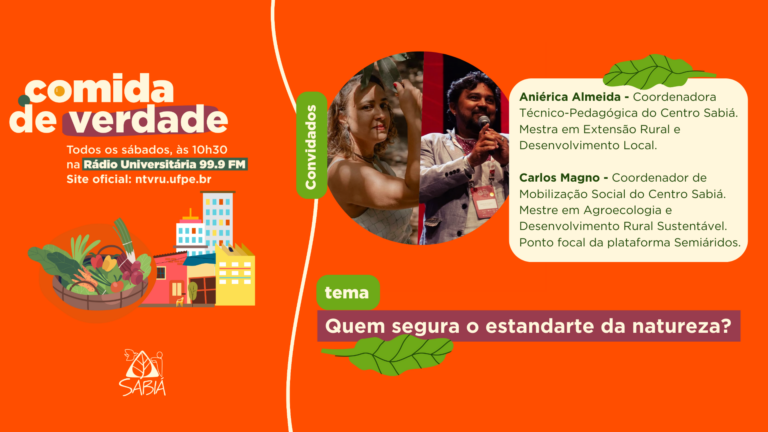

Carlos Magno was born and raised in the semiarid, is a father, coordinator of the Sabiá Agroecological Development Center and focal point of the Semiarid Platform of Latin America, Fulbrihter 2022-2023 and Rockefeller Foundation Climate Fellow.

This article was written for issue 129 of the WBO weekly newsletter, published on August 9, 2024.

To update the newsletter and receive it for free, enter your email address in the box below.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Information from the Convention of the Parties to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) warns that 70% of the world’s people who suffer from various forms of malnutrition live in dry areas, whether they are arid, semi-arid or sub-humid. This United Nations (UN) classification of drylands takes into account the amount of rainfall (pluviometry) and evapotranspiration, which results in a balance that tends to be low or negative in these zones. Drylands are spread throughout the world and cover more than 41% of the planet’s land. They are present on all continents, with large tracts of land such as the Sonoran Desert in the United States, the Sahel region in Africa and much of Australia. However, what many people don’t know is that it is in Brazil, more specifically in the Northeast, that we find the most populous semi-arid region in the world, with around 30 million people. This region has historically been known as Brazil’s “problem region”, due to successive droughts that have caused deaths and displaced millions of people in recent decades.

Despite the political, economic and media power of agribusiness in Brazil, approximately 70% of the food on the Brazilian population’s table comes from family farming. According to the FAO, data from the latest Agricultural Census in 2017 shows that half of the country’s family farming is in the Northeast. And this large territory, which is also a food producer, is threatened by a process of manipulation of its land, which is turning semi-aridity into aridity, in a process known as desertification, which was identified for the first time in Brazil at the end of 2023 between the states of Bahia and Pernambuco. In addition to all these aspects, the Semiarid’s predominant biome is the Caatinga, which in Tupy means “white forest” due to its gray color when it loses its leaves in the dry season. The main feature of this biome is that it is exclusively Brazilian, with fauna and flora adapted to these climatic conditions.

The Caatinga needs to be considered as a strategic biome in the Brazilian climate debate. It should be prioritized as a key to understanding socio-ecological resilience processes. Xerophytic plants, for example, display an incredible adaptive capacity, losing all their leaves during periods of drought to conserve water, hibernating during the dry season and storing water for more critical moments. We can also talk about the range of native bee species that have co-evolved with the plants of the Caatinga. In an era of climate change, such biological capacity becomes crucial. But unfortunately, this biodiversity continues to be undervalued and underfunded.

The current climate context also reveals a dispute over narratives and what is revealed is that the Brazilian semi-arid region has been treated as a mere generator of wind and solar energy, due to its great availability of wind and sun. However, this simplifies and underestimates its complexity. These initiatives, although important for a clean energy matrix, often do not take into account the integral conservation of the biome, generating environmental and social problems in the region. In addition, the local knowledge of the communities that inhabit the Caatinga, which over the generations has developed strategies for adapting to climatic adversities, is often forgotten, despite having incredible potential for knowledge about processes for adapting to global warming.

A clear example of this is the droughts in the Amazon, which are now beginning to gain notoriety in the press as an undeniable sign of climate change, while in the semi-arid region, transient annual droughts have always existed. Imagine how much the accumulated knowledge of these local populations could help and exchange knowledge with Amazonian populations so that we can collectively understand these characteristics that are here to stay. At the end of the day, we are one and the same people, the sertanejos and the riverside dwellers, who have never developed with CO₂ emissions, but who will be the first to suffer the impacts.

Initiatives such as the “1 Million Cisterns Program”, run by the Brazilian Semi-Arid Articulation (ASA), not only provide water through a social rainwater harvesting technology, but also promote dignity and environmental awareness. This program has already brought drinking water continuously to more than 5 million people, making it one of the largest climate change adaptation programs in the world. As well as agroforestry family farming initiatives, such as those evaluated by the Sabiá Center, which are inspired by nature and bring benefits for balanced food production.

It’s time to consider and value the Caatinga and the semi-arid region. While the world is looking for solutions to combat climate change, the Caatinga and its peoples are already offering lessons in survival, adaptation and resilience. Its role is fundamental, and it is our responsibility to bring it to the center of the climate discussion. The Caatinga cannot continue to be the forgotten biome; on the contrary, we can be one of the solutions for climate adaptation in the world.

Nothing found.